| Home > Return > |

|

| GUILLERMO MUÑOZ VERA: Imagining Geography by Edward Lucie-Smith [*] From: Arte al Día Internacional Magazine. May 2011 |

|||||||||||||||

|

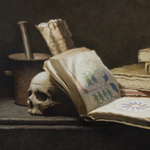

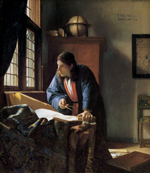

Probably the most significant item in this striking new series of paintings by Guillermo Munoz Vera is the canvas called Los Geógrafos . It is a complex composition, which shows the artist’s virtuoso powers of realistic representation at full stretch. It is also complex in its symbolism. What we see is a brick wall, which evidently belongs to a building of some age. This establishes the frontal plane of the painting. In the midst of this wall there is an opening, which we assume to be high up in the building, offering a sweeping view we are not allowed to share. The bottom part of this opening is blocked by a simple metal railing, and leaning on this railing there is a man in sober 17th century costume, looking outward, and slightly to his left. His expression is contemplative and self-contained. Behind him, we see a softly lit room, with a single candle burning on a table, which also carries a terrestrial globe, what look like maps, and a few vellum-bound books. Above the table hangs a painting, which we immediately recognize as a famous work by Vermeer – The Geographer, whose location in the real world is the Stadelsches Kunstinstitut, in Frankfurt am Main. The figure in Vermeer’s painting is generally supposed to be the microbiologist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, who was a contemporary of Vermeer in Delft, and the executor of the painter’s will. Leeuwenhoek also apparently posed for a painting that is a pair to this one, The Astrologer. Some art historians have hypothesized that Leeuwenhoek, who was also an expert in the use of lenses, helped Vermeer to make the camera oscura the artist is supposed to have used when composing his paintings. If one puts this painting in the context suggested by the title of the whole series, Terra Australis, there are several possible layers of meaning. Terra Australis was the name given to a supposed vast new continent in the southern hemisphere. The idea that there was such a body of land was first put forward by Aristotle, and later elaborated by the Greek geographer Ptolemy, who lived in the 1st century c.e. The idea that there must be such a continent obsessed many of the leading scientists and adventurers of the Age of Discovery, which stretches from the last years of the 15th century until the middle of the 18th. Some mid 16th century maps actually show its existence as a fact. Juan Fernandez, a Spanish explorer who sailed from Munoz Vera’s native Chile in 1576, actually claimed to have discovered it, and the story has resonated in Chilean imaginations ever since. In fact, it is just possible that Fernandez made the first European sighting of New Zealand, long before Captain Cook. The painting is therefore essentially a tribute to the power of the human imagination. The man in the foreground, gazing at some panorama we can’t see, is dreaming of things that don’t exist, but might exist, if he puts sufficient force of will into imagining them. If Vermeer’s subject is in fact Leeuwenhoek, this adds an interesting gloss to the situation. Leeuwenhoek is famous for his discovery of animalicules – living entities too small to be visible to the human eye. This discovery was made possible by the rapid improvement of lenses, during the period in which he lived. The invisible animalicules, metaphorically speaking, occupy a parallel universe to the one that is generally known. Another major painting, extremely ambitious because of the large number of figures it contains, is entitled El Nuevo Mundo según Lope. If refers to a well-known play by the prolific Spanish Golden age writer Lope de Vega. The full title is El Nuevo Mundo descubierto por Cristobal Colon. An audience, all male, is shown watching a representation of the play, in some cases not very attentively. And here too there is the device of a picture within s picture. Hung against the walls of the courtyard are painted cloths, one with colorful representations of ‘Indians’. The cast list of the play, when one consults it, is a strange mixture. Those who appear include Columbus himself, the King and Queen of Spain, the Duke of Medina Sidonia, the Christian Religion and Idolatry (both personified), a Demon, and, sure enough, several aboriginal inhabitants of the new world that Columbus discovered. The play is now often discussed in conjunction with Shakespeare’s The Tempest, as one of the earliest presentations of the idea of the Other – that is to say of beings viewed as being essentially excluded or alien. The idea was introduced into philosophy by Hegel. According to Hegel, an ‘I’ encounters another ‘I’ and finds that this compromises its own pre-eminence and control of the world it inhabits. The choice is either to ignore this Other, or to see it as a threat and enter into a struggle to subdue or enslave it. It is easy to see how this relates to the myth of a Terra Australis. Other paintings in the series play in a wide variety different ways with the central i ideas that have already been touched on here. Quite a number are extremely skillful still life compositions, which feature globes and related objects, such as astrolabes and orrerys. One still life, however, entitled La Arucania, features a Spanish conquistador’s morion and powder horn, contrasted with indigenous musical instruments, typical of a southern region of Chile that the Spaniards never completely conquered. The urge of conquer is paired ironically in the composition with the urge to create. Some canvases show sailing vessels at sea – historic sailing ships, not modern ones, emblematic of the adventures of early voyagers, setting out, like Juan Sanchez already mentioned, into regions of the world then still completely unknown. The paintings of the Terra Australis series are virtuoso performances, contributions to a continuing tradition of realist art that continues to flourish both in Spain and in Latin America. Yet they are also something considerably more. The realism resonates because it is the vehicle for meditations on the condition of humankind, cast adrift in and increasingly uncertain world, yet always conscious that there maybe something more, some entirely new realm, beyond the visible horizon. The paintings are Post Modern in the sense that they often make use of formulae borrowed directly from the Old Masters. This is particularly true of the still lifes, which make use of time-honored properties – a skull, an hour-glass, a pile of old books, with no modern inclusions. The compositions are often deliberately based on those used by the Netherlandish and Spanish still life painters of the first half of the 17th century – compare, for example, Munoz Vera’s Vanitas with paintings on the same theme made by Jan Davidszoon de Heem (1606-1684). Yet there is always always a note of skeptical irony that assures us that these are contemporary works, mirrors of our own restless, always dissatisfied sensibility. The elusive, forever receding great southern continent is, in the terms Munoz Vera sets out for us, still to be discovered.

[*] Born in 1933 in Kingston, Jamaica, Edward Lucie-Smith moved to Britain in 1946 and was |

|

|

| Home > Return > |