|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

THE HISTORY OF PLASTER CASTS

George Mason University

|

| |

|

Plaster Casts are the reproductions of original sculptural artwork. For centuries, artists and students have copied original masterpieces for their sense of beauty and inspiring workmanship. During the neoclassical craze of Western Europe, private individuals and museums began to collect them in large quantities. North America followed suit in the mid- nineteenth century. But the museum collections began to dwindle when they chose to stock their precious space with original sculpture works. The museum casts were either put into storage, or destroyed. Today, there is a renewed interest in antiquities, as well as an appreciation for the design quality of the casts. As a result, many plaster casts are emerging from the dusty storage spaces, and are being displayed again throughout museums and teaching institutions.

In the mid-third millennium B.C., the Egyptians first pioneered the casting method, by plastering the heads of mummies for portraits of the deceased. The Greeks, followed by the Romans, adopted the plaster techniques, as a means of reproducing copies of famous Greek marble and bronze statues. The first known location of a plaster cast collection was Imperial Rome. The collapse of the Roman Empire ended the popularity of collecting art in the Mediterranean World. In addition, the rise of Christianity largely influenced the destruction of sculptures and plaster casts, in order to conceal references to previously held pagan beliefs.

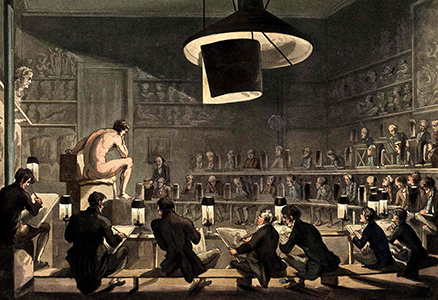

A tremendous rediscovery of antiquities occurred in 15thcentury Renaissance Europe. Art schools made use of plaster casts from recently unearthed antiquities because they felt the works of the ancients were incomparable. The effects of the sculptural rebirth began to reverberate throughout Europe in the art academies and universities. Authenticity was not a concern for most collectors, as reproductions and casts became largely desirable. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

During the 19th century in London, England, an increased interest developed in publicly displaying plaster casts. Collecting them was not only an attempt to improve art and architecture in England, but also to educate the nation and “silently, but surely raise the standard of taste in the community.” In 1881, George Gilbert Scott desired to establish an educational museum in London, the Royal Architectural Museum. By 1903, the museum had to close its doors and the collection was divided. The majority of the works went to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. That museum became an important leader in the collecting and displaying of plaster casts.

Also becoming prominent in the art of collecting and displaying plaster casts was Paris, France. During his travels in Europe, Napoleon had plaster casts made when he was unable to acquire the original sculpture work. The locations for France’s grand collection became the Ecote des Beaux-Arts and the Musee de Sculpture Comparee. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Un coin d’atelier de sculpture [1880]

by Édouard Dantan [1848-1897]

Musée des Avelines, Saint-Cloud

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

France was also responsible for the first shipment of plaster casts to the United States that arrived in February, 1806. Napoleon authorized the first shipment, which aided students in their drawing classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Between the mid-19th century—to the early 20th century, New York, Chicago, and Pennsylvania became the leading states to collection the plaster casts in the United States.

Upon his death in 1883, Levi Hale Willard bequeathed a large sum of money to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in New York. The money was intended to start a collection of “models, casts, photographs, and other illustrative of the arts.” As a consequence, in 1886, donor Henry G. Marquand requested that sculptural casts were added to this collection. The collection at the Metropolitan grew rapidly and they were exhibited in the large hall—presently known as the front hall.

By the mid-20th century, plaster casts were beginning to fall out of favor in museums. The largest reason for the change in attitude was because museums began to focus their acquisition upon works by the original hand of the sculptor. In 1949, the Art Institute of Chicago destroyed some of their plaster cast collection; maintaining that the casts were too expensive to restore, and created a fire hazard in storage. Other institutions and museums followed suit. Presently, the works that are housed in the storage spaces for the Metropolitan Museum of Art, are largely being donated to universities across the United States.

The trend in the history of collecting and displaying plaster casts both rises and falls, as many trends do. Over the course of thousands of years, the authenticity of ancient sculptural works both rose, and fell in popularity. Presently, the perception regarding ancient works—whether they are replicas or not—is changing again. Appreciation for the antique is again on the upswing!

The History of Plaster Casts

George Mason University

History & Art History Departament

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

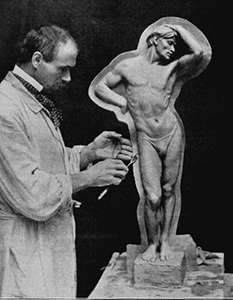

Enrico Cantoni [1860-1923]

worked with the sculptor Edouard Lanteri modelling and sculpting the human figure

|

|

|

|

| |

|

THE HUMAN ANATOMY

By Edouard Lanteri

|

| |

|

Some time ago I discovered a valuable Ecorchè hiding in a dusty corner of the workshop. My father bought it many years before in an antiquary shop and I remember it among the casts since I was a kid. I was surprised when I realized that was exactly the Anatomy of Man by the french sculptor Edouard Lanteri (1848–1917) professor at the South Kensington Arts Schools and first professor of Modelling at the College in London. I had seen it on his famous student's manual Modelling and Sculpting the Human Figure. The model is an original plaster cast signed and dated E. Lanteri 1901.

Undertaken a small restoration of this plaster model, I removed an improper layer getting in this way all the incredibles details of the modeling. I did some grouting where it was necessary and I preferred to do nothing else to preserving the precious model as it was done. Then I maked a silicon rubber mold after well protecting the original surfaces and cast a new plaster model. Now available in our collection of anatomical studies it is a beautiful piece and so useful for the study of human anatomy for the artists.

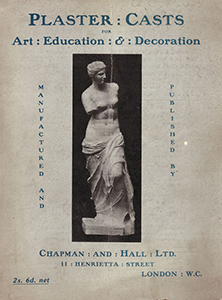

The discovery was exciting and I started some research about it. In a online bookshop I was lucky to purchase a very rare original 1902 catalog in which the Anatomy was offered for sale together with many other casts for art students. The publisher Chapman & Hall Ltd. was the same for the Lanteri's modeling manual, the Anatomy model and the Catalog of Casts. |

|

| |

|

|

| |

Edouard Lanteri [1848-1917]

Edouard Lanteri was a French-born British sculptor and medallist whose romantic French style of sculpting was seen as influential among exponents of New Sculpture. Lanteri's sculptures were mainly modelled in clay before being cast in bronze, though he would also work in stone. He produced portrait busts, statuettes and life size statues.

As of 1880 he taught at the National Art Training School in South Kensington (later renamed the Royal College of Art) and in 1900 became the College's first Professor of Modelling (1900-10); in this role he was involved with the architectural and decorative sculpture for Sir Aston Webb's Victoria & Albert Museum, London

Source: Wikipedia |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

During my research study I found the sculptor's moulder. An italian skilled craftsman named Enrico Cantoni (1860-1923) emigrated to London in the late nineteenth century. He was teacher of casting and molding at the Central School of Arts and Crafts around 1909 and worked as 'moulder' for the Royal College of Art (including the National Art Training School) around 1904. Enrico Cantoni worked a lot with Lanteri and through some photos that show him working I could understand his way and technique of working. By comparing his technique with the original anatomy model I found many similarities. I could say, it is very likely, that the model found was maked by Cantoni as all casts sold by Chapman & Hall Ltd.

Anatomy of Man by Edouard Lanteri

Felice Calchi - The plaster casting journal |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

MAJESTY AND STRENGTH - JUPITER OF OTRICOLI PLASTER CAST

This is one of the best head of Jupiter and at first was supposed to be the most faithful reproduction of the Zeus of Olympia by Phidias. Many historical artistic considerations and the comparison with the type of the Phidias Zeus on some coins of the epoch of Hadrian and one of the epoch of Septimius Severus, have excluded this opinion, and now this type is supposed to represent a transformation of that Phidias which was carried out by the second Attic school in the middle of the fourth century b.C. However this may be, this head is a masterpiece of conception and execution. To be well appreciated, it must be seen from a distance and we must imagine it, placed higher, upon a complete figure sitting on a throne.

The height of the forehead, the abundance of the hair and beard, the deep eyes in which is veiled a vibrating look that loses itself mystery, give to the statue an impression of majesty and strength, joined with grace and wisdom.

"He spoke, and the great son of Saturn knitted his dark brows, shook the ambrosial locks on his immortal head,and all the vast Olympus trembled." (Homer)

This verse have been often repeated in connection with this head and we must confess that they suit it perfectly.

Majesty and Strength - Jupiter of Otricoli Plaster Cast

Felice Calchi - The plaster casting journal

Traducción: A. García

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|

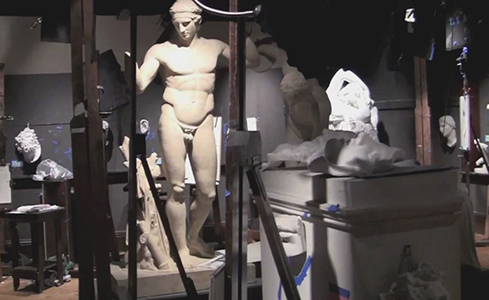

FUNDAMENTOS DE LA FORMA: DIBUJO Y ESCULTURA

Beaux-Arts Atelier. NY

A view into the cast hall and sculpture studio, where Beaux-Arts Atelier students work alongside those of the Grand Central Academy of Art, the ICAA's fine arts division. Instructors Angela Cunningham and Mason Sullivan guide students in the sister arts of drawing and sculpture as they work from the ICAA's historic

Foundations of Form: Drawing and Sculpture

Beaux-Arts Atelier. NY

|

|

|

| |

|

| |